For now we’ll let Harry, our up-and-coming polo star, park his bike and let us focus instead on advancing your shooting.

This is about your shooting, not the guy’s shooting standing next to you in the queue for stand 4 whose tricked-up Perazzi you’ve just noticed. Nor is it the guy telling an already hard-pressed picker-up that there’s “a few” partridges down “somewhere along” that far-off hedgerow. (The picker-up’s the one without the 20 bore, trying not to telegraph body language that says: “No, you really haven’t!”)

This piece concerns itself with a single factor, the only one amenable enough and sufficiently malleable to change your shooting for the better: you. Shooting well means getting properly to grips with a set of task-specific skills.

Skills are like tools. Like tools, skills can be acquired, maintained, their use understood, practised and, eventually, mastered.

Like tools, skills can be misunderstood, misused, neglected and, even if once found to work well, can be lost altogether. Skills can be built upon. Skills are perishable.

You will appreciate by now that success in shooting requires aptitude, time, effort and commitment. There is no easy road, only work and a great deal of it. Here’s something to help you in your development: A E I O U. Got it? Now let’s get you moving in the right direction.

ALL of this, everything, is about you

Now I‘ve softened you up for the ownership of this one at the very beginning. And why? Well, this is perhaps the easiest one to lose sight of.

There is a responsibility here for progress. If you really want to shoot to a high standard then you have to go after this as a goal. Whether you manage to stand up in your ambition or fall flat on your back trying, you must give it nothing less than your best. You must also BELIEVE that you can: as Henry Ford once rather grittily observed: “Whether you think you can, or whether you think you can’t — you’re right!”

The Eyes have it

I have not ranked factors here in any order of priority, but if I had, this one would be right at the top: EYES. Rather more accurately what I mean here is shooting vision. In the thirty-odd years since the Guildford gun-maker S.R. Jeffery first taught me to fit shotguns, I have found vision in shooting to be the greatest single limiting factor to potential.

You will hear plenty on the subject of eyes and shooting. Like all thorny perennials it’s one that keeps resurfacing. Vision performs a highly complex function in the use of a shotgun, and is far from simple for many. Confusing and contradictory advice regularly makes the matter worse.

You MUST get shooting vision right in order to progress. Assess this issue thoroughly, to the extent that evidence is gathered and any correction strategy explored fully. The Worshipful Clan of the Howling Moon-Bear may well slavishly adhere to their Grand-mantra: “everyone-must-shoot-both-eyes-open!” The shooting media is awash with it I know, but the fact of the matter is many of us can’t and don’t. Find out for sure. Manage vision if needs be. Stick with it. Crack on. Hit more.

We take the 'i' and turn it through 180 to create a model

The '•' represents you: the place your shooting is right now and from where you seek to move forward. The 'Ι' placed above and ahead of you represents the great column of time and effort — perhaps all of those 10,000 hours-at-practise we’ve defined already - necessary to get you where you want to go.

Once kindled success has a defined momentum, and once underway ambition is an impatient force. There are no shortcuts, but it is possible to prune the 'I' - in practice ‘topping-and-tailing’ it. It is possible to CHUNK more rapid progress at key points.

At the base of the 'I' are critical near-term aims: core skills you MUST secure. Some skills can be perfected without physically shooting. Gun handling is a very good example: your shotgun must become a uniquely familiar object if you intend to shoot well. Handle a gun every day, and several times a day is better still: you groove this one to the point of obsession.

Now we may look to the top of the 'I' - that far-off goal that pulls ambition on and up. A trend in performance training suggests we all must “try for the moon but aim for the stars anyway!” That probably has merit if you are part of a sales team that means to sell stuff; it has less value in shooting where all goals - even ones far off in the future - need to be framed with certainty.

Aiming at gold is fine for some, with a complete understanding of the resource requirement necessary to get there. For others the ambition of becoming a solid B-class shot, affording to shoot twice in a month, is equally fine. In relative terms the undertaking in both is substantial. We must know WHERE we’re going and HOW to get there: the '•' ➔ 'Ι' model reflects this.

Build experience towards improvement

Circular models in learning imply cycles, and these represent powerful mechanisms for improvement. In terms of securing and perfecting skills our brains are programmed to work by building EXPERIENCE toward IMPROVING. In other words, doing something well enough to become efficient at it; so efficient in fact, that ability is acquired and talent recognised.

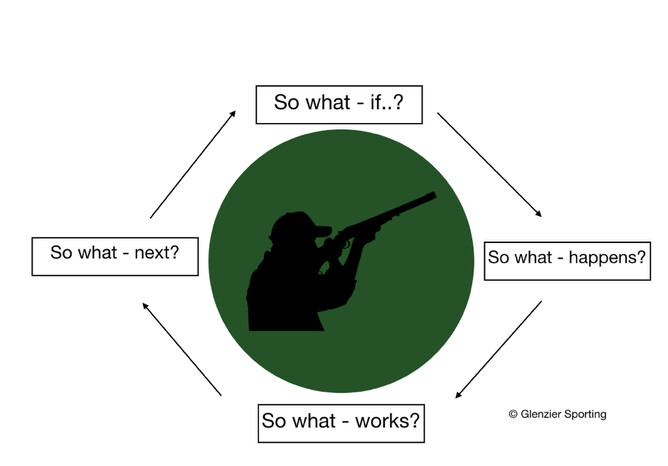

In learning to advance shooting skills at any level we must seek and act upon one critical question - SO WHAT?

Actual progress in shooting comes down to finding out for yourself just how to make it all work. The more we study top end performance, the more we appear to find that the individual’s own experience of what is happening when shooting is oddly quite vague. Moreover, the very best shots actually seem to be consciously aware of the least.

There will come a point where you must actively experiment with your shooting in order to push at excellence. Change - doing things differently - is something that is not only necessary but also essential to development. High order shooting expertise is an accomplished skill-set established by dynamic challenge. The “So what?" cycle is designed to enable ‘progress-through-challenge,’ thereby driving your shooting forward.

Understand what all this means

The higher we go the tougher it gets. This is why a commitment to succeed is such a vital characteristic to securing high-end achievement.

For example, Harry’s bike: we left it back at the beginning. Purposely modified to be unstable, Harry’s bike is very different. With a shortened mallet and a tennis ball, Harry mounts his wobbly bike to ‘dribble’ all the way from stables to his lodgings, there and back on the estate-track for nearly a mile. Harry does this not to consolidate his core skills, rather to deliberately challenge them.

Nothing about this exercise will resemble anything that Harry encounters on the polo field: a bike is not a horse, the mallet handles appallingly, and the skittering ball defies control. Harry dislikes the exercise, he would rather not do it, and it would be so very easy not to. The actual value of this to Harry is that he must force himself to do it - every time. If there’s a Zen philosophy to any part of driving toward excellence, you’ve got it right there!

“Your best teacher is your last mistake.” - Ralph Nader

Enjoyed this article and want to know more?

Why not contact us at Glenzier Sporting. Mike Smith has run the Whithorn shooting ground for 20 years and offers teaching lessons and gun fitting.